After the release of my new book, Teaching Coding through Game Creation, I was thrilled to be invited to write an article on the topic for VOYA Magazine. The article, “Game Coding for the Win!” appears in this month’s (June, 2019) issue and presents both an argument for coding clubs in libraries and a step by step guide that youth librarians can use to teach their first game coding class.

Author: sarahkepple

Coding is the New Cursive: Writing a Pathway for Digital Citizenship

One of the beautiful things about America is that we provide free and compulsory schooling, which, theoretically, is supposed to produce an educated voting base. Whether that actually happens or not is a topic for a different day, but one thing that certainly does happen is that as adults we all have strong opinions about what school should be based on our own experiences. Over the last few years two subjects continuously pop-up for debate, cursive and coding.

Extras or Essentials?

Cursive and computer science are not mutually exclusive subjects. A school system could certainly teach both, and contrary to the misleading mantra that “schools don’t teach cursive anymore”, many do. I compare them, however, because both could be seen as “extras”, but also represent skill sets valuable and unique to their respective times. At one point in our not too distant past, handwriting in general and cursive in particular were key to communicating effectively and participating in society. Likewise, computer science skills are now essential tools to engage fully in our modern world. It’s true that the Common Core State Standards omit mention of cursive writing and includes keyboarding as essential, but this is simply replacing one finite, small motor task with another. Like cursive, the Common Core largely ignores Computer Science apart from urging educators to integrate technology.

Digital Citizenship

To provide the how of computer science education, the non-profit International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) created the most widely recognized and adopted standards to guide technology education in schools. One of their major points of emphasis is Digital Citizenship, a point shared by the American Association of School Librarians Standards for the 21st Century Learner. The information and technology educators of the ISTE and AASL recognize the need for students to be able to fully engage with a diverse digital world. This includes ethical issues such as avoiding plagiarism, understanding digital content licensing and respecting intellectual freedom, as well as communication and collaboration behaviors such as seeking out and respecting diverse viewpoints and participating in personal learning networks and community discussions.

![]()

Proponents of teaching cursive in schools argue the fair point that students should be able to decipher historical documents, primary sources like the Declaration of Independence or their grandparents’ war time correspondence. These examples rely on an ability to read cursive, but what they’re really emphasizing is information literacy, the ability to conduct research, analyze, synthesize and evaluate sources. Consider the even broader ramifications for those without these digital citizenship skills. According to a 2014 study commissioned by the American Press Institute and the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, “7 in 10 adults under age 30 say they learned news through social media in the last week.” When combined with the Indiana University discovery that that “people who seek out news and information from social media are at higher risk of becoming trapped in a “collective social bubble” compared to using search engines,” it becomes clear that the constant regurgitating of disreputable information among insular online groups is not the way to move our democracy forward into productive discussion. Rich computer and information science education in the area of digital citizenship helps information seekers both recognize trustworthy sources and engage with others fruitfully in online environments.

A Little Bit Goes a Long Way

For some students, their future digital engagement may be limited to using prebuilt forums and tools, yet possessing some basic coding skill opens up future possibilities for digital citizens, just as reading cursive opens up access to the past. Knowing a little code allows technology users to break free of many constraints, but more importantly, those with some coding experience have a better understanding of some of the critical intellectual freedom issues facing our society today. Is Apple right that creating a backdoor for the FBI would be disastrous for security? What is the hacker group Anonymous really doing when they say that they’re going to take on Isis or the KKK? What does Open Source really mean, and who owns my contributions? Those who can code are also in the position to create their own content, from video games to apps to robots and innovations. Sure, not everyone will become a professional computer engineer, but everyone benefits from some knowledge. Not everyone needs to be an accountant, but we all have to pay taxes.

But if I had to choose…

I’ll admit it; I’m a little skeptical that everyone needs to learn cursive. Most of us don’t even sign our names in anything remotely resembling the cursive we were taught in school, and more and more important documents, such as taxes, can be digitally signed. I appreciate the beauty of good penmanship, and I experience a certain nostalgia reading family history in my grandmother’s lovely hand. I also think calligraphy is aesthetically pleasing, and I’m impressed by the illuminated manuscripts of the middle ages, but the invention and use of the printing press was a more widely impactful technology that led to greater societal knowledge. So, while I don’t think there necessarily needs to be a competition between cursive and keyboard, if I were forced, as many school districts with limited budgets and time are, I would choose keyboarding every time. Why? Because keyboarding is a gateway to information and technology literacy, computer science, coding, digital citizenship, all of it. Still, the keyboard is only the currently predominate input mode to interact with computers. Voice commands, touch screens and other alternative methods may someday soon surpass keyboarding. So, rather than attaching ourselves to a particular tool, let’s think about our desired outcomes.

The point of keyboarding is to be able to interact with the computer and through it, the world. When we talk about coding in colloquial terms, we’re talking about playing around with computer programming, creating self-driven knowledge and building real-world solutions. This past week I led the second session of a video game creation class for 7-10 yrlds. In the first class, students were learning how the programming environment worked. We talked through basic components of making a game, how to program objects to move using common commands and screen coordinates, order of operations, etc… It was wonderful to see the their glowing faces as they created something that could be recognized as a game, but when they returned for the second class I was pumped to watch them independently dive in and attempt customizations, see them collaborate to figure out solutions, and best of all, vocalize to me and to each other why something worked or didn’t. These are students who, if they continue on this path, will enter their chosen professions fearlessly. They’ll be able to use the logic and lifelong learning skills they strengthened in computer science class to create websites for their small businesses, design and program clean energy solutions for their homes, and create 3 dimensional learning environments in which their children will learn. Who knows, they may even create lessons on cursive.

Prevent the Greatest Minds of Our Generation from Being Destroyed.

YOU ARE 14.

You’ve researched the possibilities, and worked hours on a solution. After singeing your fingers soldering wires together and assembling parts that you worked extra chores to purchase, you finally finish assembling and testing your masterpiece. It works! It really works, and YOU made it. You want to show it off to someone who will appreciate it, so you delicately pack it up and take it in to school with you.

Walking into school you’re jittery with excitement. This will be the moment when your new teacher sees how serious you are and you find your niche among your classmates. You carefully place your invention in your locker as you gather your books for your first few classes. You painstakingly carry your invention to class, tip toeing over couples making out, jocks wrestling and people walking obliviously against the flow of traffic.

You get there, SO EXCITED to show your teacher and your classmates what you’ve made. Once the other students see it, they’ll be so excited about what you can do, that they’ll want to discuss it with you. It’s been hard to be the new kid at a new school as a freshman.

Tick. Tick. Tick.

You fidget all through roll call. As soon as the teacher is done, you shoot up your hand, unable to wait one more moment. “I have something I’d like to show you, please.”

This is where it all goes wrong. So terribly, terribly wrong.

You pull your invention out of it’s casing, and begin to describe it, but before you can get into any depth, two students gasp, and others exchange looks. The teacher frowns and clears a throat full of discomfort. “What exactly do you have there?”

“It’s a clock! I made it myself!”

Tick. Tick. Tick.

Furrowed brows. Pause. “It’s a clock.”

It’s unclear if this is a statement or a question. Someone giggles a nervous laugh. This is not at all the way that you thought this would go. What is happening?

You get even more confused when a few minutes later a police office stands in front of you.

“What do you have here?”

“It’s a clock.”

“A clock, eh?”

pause

“Answer me.”

“Oh, um, yes, so it’s a clock. I made it myself.”

“Some people are scared that it might be more than a clock.”

“More than a clock?”

pause.

“It could be a bomb.”

nervous laughter

“A bomb?”

“It could be.”

“It’s a clock. I made it. I wanted to show my teacher and the other students in my class.”

pause.

“A clock, eh?”

The next thing you know you’re being hauled out of school in handcuffs. In horror, your sister takes a picture and texts it to your parents. This is your only hope, but you still can’t process what is happening.

Create, they said.

Innovate, they said.

Why am I being fingerprinted? Why am I getting suspended?

Bizarre, isn’t it? Unfortunately, this drama is based on the real story of a real teen.

It happened Monday. Ahmed Mohamed made a clock. When we was arrested for bringing it to school, he showed us all what time it is.

You can be brave.

Makers are the future. They need to be understood and encouraged, not feared. One thing that has gotten buried in this story is that the student’s engineering teacher was impressed, but advised the student not to show the clock to other teachers, presumably because they wouldn’t understand it and would react poorly. It’s fair to say that the engineering teacher was right. Though the teacher who was afraid the clock might be a bomb and the administrator(s) who called in the police were probably acting out of an “it’s better safe then sorry” mentality, the bottom line problem is that they didn’t understand that what they were seeing was safe, or even which colleagues to ask for an expert opinion, say like an engineering teacher…

You can question the status quo.

We are at a critical point in education. The point of public schooling used to be to prepare students for static jobs, whether in a factory or an office. These jobs required very specific, domain level knowledge that could be passed down from the sage on the stage, memorized and regurgitated. The reality is that jobs are not like that now. No job requires a person to be knowledgeable in math and only math or English and only English. Schools have become an artificial construct. If the point of school is to prepare students for the “real world” including college and careers, we need to rethink the educational hierarchy.

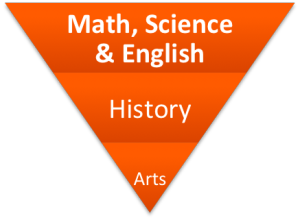

At the dawn of the industrial revolution, and probably before, the hierarchy looked something like this in most if not all western schools:

Figure 1: Industrial Education Hierarchy

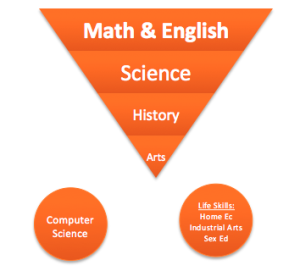

This model reflected the needs of industrial barons and a people in a space race. Over time, however the needs have shifted, and pressures on the education system have shifted the model to something like this:

Figure 2: Post Industrial Education Hierarchy

Schools are trying hard trying to do everything, but as a whole, they’re still doing it in a framework that is ill suited to the needs of modern students and future workers. We must rethink not only the hierarchy, but also the subject silos and our education methods. I propose three new core subjects and a new model.

Communication and Information Literacy

Language, Computer Science, Library Science, History, Arts

In a society that is in constant communication with devices, 24-hour news, streaming media the ability to access, evaluate, analyze, use and contribute information is key to a thriving democracy. Students can write songs, create videos, publish research and connect ideas.

Making

Arts, Computer Science, Industrial Arts, Science, Math, Library Science, History, Language

To make, um, let’s say a CLOCK, a student would research the history of clocks, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, coding options and fabrication methods. To make a theatrical set, a student would need to understand the context of it’s role in the play, research historical accuracy, learn to use power tools safely, take accurate measurements and work with ratios and produce 3d effects with paint.

Wellness & Life Preparedness

Health, Physical Education, Home Ec, Sex Ed, Math, Science, Arts, Library Science

In his now famous Ted Talk from 2006, Sir Ken Robinson wondered why physical subjects, such as dance are relegated to the bottom of the educational hierarchy even though we all have bodies. Since then, we’ve also found ourselves in a national health crisis with childhood obesity on the rise, and an ever-increasing need for health care professionals. In fact, seven of the ten fastest growing jobs according to the U.S. Department of Labor are in the health and wellness field. Imagine a class in which students learned about their bodies, how they work, and how to use and care for them. We’ve also been in a bit of a financial crisis. Instead of making everyone take advanced math classes that, truthfully, most won’t ever use, perhaps we should focus on personal economics and global finance, which affects everyone. Some students would still study higher-level math, just as some students would study higher-level music.

Let us create a new structure for learning, one that puts the student at the center.

Figure 3: Information Age Learning Collaborative

If we are to be focused on the needs of students and preparing them for the world they’re facing, we as educators need to break tradition, step out of our comfort zones, and work together in a new structure.

Yes, I know that this model would require a complete shift in the school days, with teams of teachers working with groups in block schedules, but we need to make a fresh start. We have already pulled the foundation out from under schools and expected them to stand. This isn’t a renovation project. It is time to rebuild it, and rebuild it in a way that makes sense. Our students are counting on us.

Abolish Standardized Tests

While I agree that it’s important to evaluate student progress and to evaluate teacher performance, standardized tests do neither. No student is “standard.” Teaching to the average teaches to no one, because there is no average student. There are some great articles about this, but Harvard professor Todd Rose gives a great overview. If we really want to evaluate how much and what students are learning, how about we see what they can do? Talk with students about their science fair projects, go to see robotics teams in action, watch the plays that students have written and performed. If we shift our focus to what individual students can do, instead of how they measure up to an imaginary average student, we can make school a launching pad for futures beyond our wildest expectations, instead of a training ground for a world that doesn’t exist.

YOU CAN HELP.

- You can think deeply about the types of skills that you as an adult use or need most, and you can share that with school officials and policy makers.

- You can listen to educators in and out of schools who are making a difference, and ask them how they do it, what they need and how we support them.

- You can listen to students about their needs and interests, and help them learn it or connect them to someone who can.

- You can be grateful for the incredible communication tools of smart phones and social media that allowed this child to receive instant support from President Obama, Mark Zuckerberg and many others. You can encourage schools to use digital tools to build skills rather than be afraid of them.

- You can advocate for cross-curricular learning instead of test driven silos.

- You can demand that elected officials abolish standardized tests and reshape learning objectives.

- You can share this article.

- You can join the conversation by replying.

It’s time to stop living in the shadow of the Industrial Revolution, and instead forge an Education Revolution.